Code Layout#

The PyLith software suite is composed of a C++ library, Python modules, a Python application, and a few Python preprocessing and post-processing utilities.

Directory Structure#

The C++, Python, and SWIG Python/C++ interface files all sit in different directories. Similarly, the unit tests, MMS tests, full-scale tests, examples and documentation are also in their own directories.

pylith/

├── ci-config # continuous integration testing configuration

├── docker # Dockerfiles for creating Docker images

├── developer # Utilities for developers

├── docs # Documentation source code

├── libsrc # C++ source for library

├── modulesrc # SWIG interfaces files for C++ Python bindings.

├── pylith # Python source code for PyLith modules.

├── applications # Source code for command line programs

├── m4 # Autoconf macros

├── share # Common parameter settings

├── examples # Example suite

└── tests

├── libtests # C++ unit tests

├── pytests # Python unit tests

├── mmstests # C++ Method of Manufactured solution tests

├── fullscale # Automated full-scale tests

└── manual # Manual full-scale tests

We use the Pyre framework (written in Python) to collect all user parameters and to launch the MPI application. As a result, the top-level code is written in Python. In most cases there is a low-level C++ object of the same name with the low-level implementation of the object. We limit the Python code to collection of the user parameters, some simple checking of the parameters, and passing the parameters to the corresponding C++ objects.

The C++ library, SWIG interface files, and Python modules are organized into several subpackages with common names.

bc Boundary conditions.

faults Faults.

feassemble General finite-element formulation.

fekernels Finite-element pointwise functions (kernels).

friction Fault constitutive models.

materials Material behavior, including bulk constitutive models.

meshio Input and output.

problems General problem formulation.

testing Common testing infrastructure.

topology Finite-element mesh topology.

utils General utilities.

Code Structure#

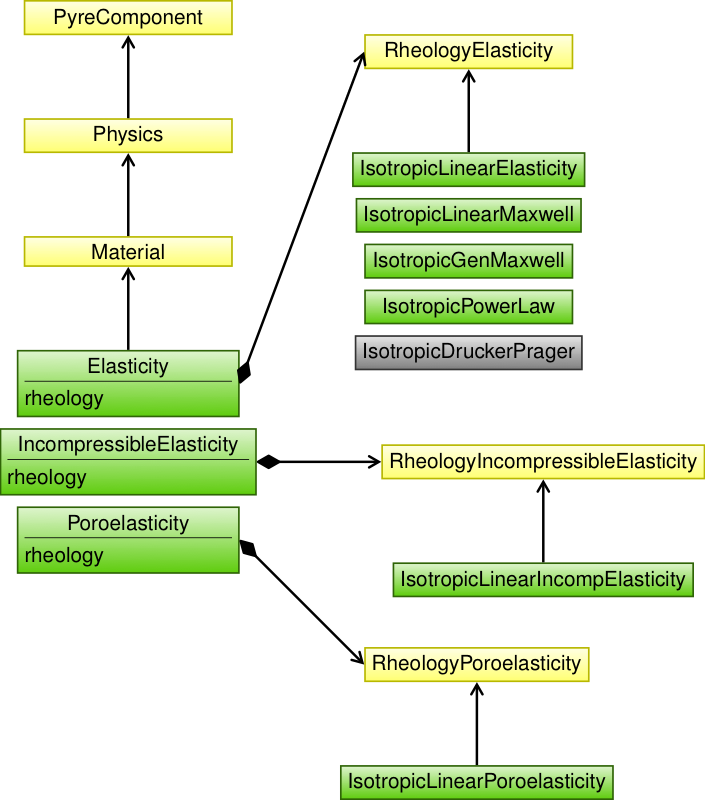

Legend for class diagrams#

Abstract classes are shown in the yellow boxes.

Concrete classes are shown in the green boxes.

Inheritance is denoted by an arrow.

Aggregation is denoted by the a diamond and arrow.

Application#

Fig. 136 Diagram showing the relationships among objects associated with PyLithApp.#

Problem#

Fig. 137 Diagram showing the relationships among the Python and C++ Problem objects and their data members.#

Physics and Finite-Element Objects#

We separate the specification of the physics from the finite-element operations.

That is, we have one set of objects that specify the physics through materials, boundary conditions, and faults; another set of objects perform the finite-element operations required to solve the equations.

Fig. 138 illustrates this separation.

The user specifies the parameters for the Physics objects, which each create the appropriate integrator and/or constraint via factory methods.

Fig. 138 Diagram showing the relationships among objects specifying the physics and the finite-element implementations.#

We generalize the finite-element operations into two main classes: Integrator and Constraint.

The Integrator is further separated into concrete classes for performing the finite-element integrations over pieces of the domain (IntegratorDomain), pieces of the domain boundary (IntegratorBoundary), and interior interfaces (IntegratorInterface).

We implement several kinds of constraints, corresponding to how the values of the constrained degrees of freedom are specified.

ConstraintSpatialDB gets values for the constrained degrees of freedom from a spatial database; ConstraintUserFn gets the values for the constrained degrees of freedom from a function (this object is widely used in tests); ConstraintSimple is a special case of ConstraintUserFn with the constrained degrees of freedom set programmatically using a label (this object is used for constraining the edges of the fault).

Problem holds the Physics objects as materials, boundary conditions, and interfaces.

During initialization of Problem, each Physics object creates any necessary Integrator and Constraint objects to implement the physics.

For example, a material will create an IntegratorDomain object that performs integration over that material’s cells.

Materials#

Fig. 139 Diagram showing the relationships among objects associated with materials.#

Boundary Conditions#

Fig. 140 Diagram showing the relationships among objects associated with boundary conditions.#

Interior Interfaces (Faults)#

TODO

Add class diagram and discussion for FaultCohesiveKin, KinSrc.

Mesh Importing#

Fig. 141 Diagram showing the relationships among objects associated with mesh generation and importing.#

Output#

Fig. 142 Diagram showing the relationships among objects associated with output.#

PyLith Application Flow#

The PyLith application driver performs two main functions.

First, it collects all user parameters from input files (e.g., .cfg files) and the command line, and then it performs from simple checks on the parameters.

Second, it launches the MPI job.

Once the MPI job launches, the application flow is:

Read the finite-element mesh;

pylith.meshio.MeshImporter.Read the mesh (serial);

pylith::meshio::MeshIO.Reorder the mesh, if desired;

pylith::topology::ReverseCuthillMcKee.Insert cohesive cells as necessary (serial);

pylith::faults::FaultCohesive.Distribute the mesh across processes (parallel);

pylith::topology::Distributor.Refine the mesh, if desired (parallel);

pylith::topology::RefineUniform.

Setup the problem.

Preinitialize the problem by passing information from Python to C++ and doing minimal setup

pylith.Problem.preinitialize().Perform consistency checks and additional checks of user parameters;

pylith.Problem verifyConfiguration().Complete initialization of the problem;

pylith::problems::Problem::initialize().

Run the problem;

pylith.problems.Problem.run().Cleanup;

pylith.problems.Problem.finalize().Close output files.

Deallocate memory.

Output PETSc log summary, if desired.

In the first step, we list the object performing the work, whereas in subsequent steps we list the top-level object method responsible for the work.

Python objects are listed using the path.class syntax while C++ objects are listed using namespace::class syntax.

Note that a child class may redefine or perform additional work compared to what is listed in the parent class method.

Reading the mesh and the first two steps of the problem setup are controlled from Python. That is, at each step Python calls the corresponding C++ methods using SWIG. Starting with the complete initialization of the problem, the flow is controlled at the C++ level.

Time-Dependent Problem#

In a time-dependent problem the PETSc TS object (relabeled PetscTS within PyLith) controls the time stepping.

Within each time step, the PetscTS object calls the PETSc linear and nonlinear solvers as needed, which call the following methods of the C++ pylith::problems::TimeDependent object as needed: computeRHSResidual(), computeLHSResidual(), and computeLHSJacobian().

The pylith::problems::TimeDependent object calls the corresponding methods in the boundary conditions, constraints, and materials objects.

At the end of each time step, it calls problems::TimeDependent::poststep().

Boundary between Python and C++#

The Python code is limited to collecting user input and launching the MPI job. Everything else is done in C++. This facilitates debugging (it is easier to track symbols in the C/C++ debugger) and unit testing, and reduces the amount of information that needs to be passed from Python to C++. The PyLith application and a few other utility functions, like writing the parameter file, are limited to Python. All other objects have a C++ implementation. Objects that have user input collect the user input in Python using Pyre and pass it to a corresponding C++ object. Objects that do not have user input, such as the integrators and constraints, are limited to C++.

The source code that follows shows the essential ingredients for Python and C++ objects, using the concrete example of the Material objects.

Warning

The examples below show skeleton Python and C++ objects to illustrate the essential ingredients. We have omitted documentation and comments that we would normally include, and simplified the object hierarchy. See Coding Style for details about the coding style we use in PyLith.

Important

Consistent inheritance between C++ and Python is important in order for SWIG to generate a Python interface that is consistent with the C++ interface.

from pylith.problems.Physics import Physics

from .materials import Material as ModuleMaterial

# Python objects should inherit the corresponding SWIG interface object (ModuleMaterial).

# Python object inheritance should match C++ object inheritance.

class Material(PetscComponent, ModuleMaterial):

# Pyre inventory: properties and facilities

import pythia.pyre.inventory

materialId = pyre.inventory.int("id", default=0)

materialId.meta['tip'] = "Material identifier (from mesh generator)."

label = pyre.inventory.str("label", default="", validator=validateLabel)

label.meta['tip'] = "Descriptive label for material."

# Public methods

def __init__(self, name="material"):

Physics.__init__(self, name)

def preinitialize(self, problem):

Physics.preinitialize(self, problem)

ModuleMaterial.setMaterialId(self, self.materialId)

ModuleMaterial.setDescriptiveLabel(self, self.label)

#if !defined(pylith_materials_material_hh) // Include guard

#define pylith_materials_material_hh

#include "materialsfwd.hh" // forward declaration of Material object

#include "pylith/problems/Physics.hh" // ISA Physics

class pylith::materials::Material : public pylith::problems::Physics {

friend class TestMaterial // unit testing

public: // public methods

// Constructor and desctructor

Material(void);

virtual ~Material(void);

// Method to deallocate PETSc data structures before calling PetscFinalize().

virtual void deallocate(void);

// Accessors

void setMaterialId(const int value);

int getMaterialId(void) const;

void setDescriptiveLabel(const char* value);

const char* getDescriptiveLabel(void) const;

void setGravityField(spatialdata::spatialdb::GravityField* const g);

// Initialization

virtual pylith::feassemble::Constraint* createConstraint(const pylith::topology::Field& solution);

protected: // protected members

spatialdata::spatialdb::GravityField* _gravityField; ///< Gravity field for gravitational body forces.

private: // private members

int _materialId; ///< Value of material-id label in mesh.

std::string _descriptiveLabel; ///< Descriptive label for material.

private: // not implemented

Material(const Material&); ///< Not implemented.

const Material& operator=(const Material&); ///< Not implemented

};

#endif // pylith_materials_material_hh

// Information about local configuration generated while running configure script.

#include <portinfo>

#include "Material.hh" // implementation of object methods

#include "pylith/utils/journals.hh" // USES PYLITH_COMPONENT_*

#include <cassert> // USES assert()

#include <stdexcept> // USES std::runtime_error

pylith::materials::Material::Material(void) :

_gravityField(NULL),

_materialId(0),

_descriptiveLabel("") {}

pylith::materials::Material::~Material(void) {

deallocate();

} // destructor

void

pylith::materials::Material::deallocate(void) {

PYLITH_METHOD_BEGIN;

pylith::problems::Physics::deallocate();

_gravityField = NULL; // :TODO: Use shared pointer.

PYLITH_METHOD_END;

} // deallocate

void

pylith::materials::Material::setMaterialId(const int value) {

PYLITH_COMPONENT_DEBUG("setMmaterialId(value="<<value<<")");

_materialId = value;

} // setMaterialId

int

pylith::materials::Material::getMaterialId(void) const {

return _materialId;

} // getMaterialId

void

pylith::materials::Material::setDescriptiveLabel(const char* value) {

PYLITH_COMPONENT_DEBUG("setDescriptiveLabel(value="<<value<<")");

_descriptiveLabel = value;

} // setDescriptiveLabel

const char*

pylith::materials::Material::getDescriptiveLabel(void) const {

return _descriptiveLabel.c_str();

} // getDescriptiveLabel

void

pylith::materials::Material::setGravityField(spatialdata::spatialdb::GravityField* const g) {

_gravityField = g;

} // setGravityField

pylith::feassemble::Constraint*

pylith::materials::Material::createConstraint(const pylith::topology::Field& solution) {

return NULL;

} // createConstraint

SWIG Interface Files#

SWIG interface files are essentially stripped down versions of C++ header files. Because SWIG only implements the public interface, we omit all data members and all protected and private data methods that are not abstract methods or implement abstract methods.

// The class declaration must appear within the appropriate namespace blocks.

namespace pylith {

namespace materials {

class Material : public pylith::problems::Physics {

public: // public methods

// Constructor and desctructor

Material(void);

virtual ~Material(void);

// Method to deallocate PETSc data structures before calling PetscFinalize().

virtual void deallocate(void);

// Accessors

void setMaterialId(const int value);

int getMaterialId(void) const;

void setDescriptiveLabel(const char* value);

const char* getDescriptiveLabel(void) const;

void setGravityField(spatialdata::spatialdb::GravityField* const g);

// Initialization

virtual pylith::feassemble::Constraint* createConstraint(const pylith::topology::Field& solution);

};

}

}